Retinal vein occlusions usually occur in people over 50 years old and are commoner in people with high blood pressure (hypertension) and high cholesterol. These may be under treatment at the time of diagnosis or may yet be undiagnosed.

Patients usually describe a sudden painless blurring of vision in one eye that may affect near and distance vision. Sometimes this is not noticed until the unaffected eye is covered by chance. This blurring does not usually change very much over the first few weeks. It is very important, though, to be seen urgently as these symptoms are very similar to those of other conditions that may need immediate or urgent treatment.

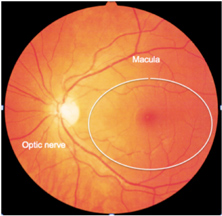

Normal Retina

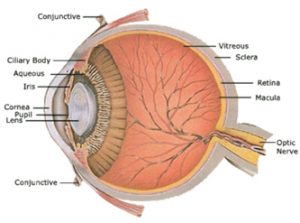

The retina has light sensitive cells, known as photoreceptors. The central area of the retina is the “macula” and contains the highest concentration of photoreceptors and gives the best quality of vision.

The light received by the photorecptors, leaves the retina via the optic nerve and enters the brain, where it is analysed to form an image. The optic nerve is also a conduit for major blood vessels to enter and leave the eye. These vessels supply nutrition to the retina and ensure healthy function. The main blood vessels are known as the central retinal artery (brings blood into the eye) and the central retinal vein (takes blood out of the eye).

These vessels divide as they leave the optic nerve to supply the different parts of the retina. These divisions are known as branch retinal arteries and veins. They are often intimately related and cross each other.

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) are both blockages the veins of the retina. The blockage in both is thought mainly to be due to pressure on the vein from outside (usually where the artery crosses the vein). If the compression occurs in the retina, this may lead to a blockage in the branch retinal vein (BRVO), whilst if the compression occurs in the optic nerve, a CRVO may result.

Branch retinal vein occlusion

In the case of BRVO, one of the branch retinal veins has an overlying retinal artery that may become thicker and ‘hardened’ and compress it. This can suddenly stop the blood flowing through the vein and lead to a pressure build-up in the smaller veins and capillaries that drain through it. This leads to tiny spots of bleeding in the retina at the time of the occlusion (blockage) as well as leakage of fluid from the capillaries (due to a build up in pressure).

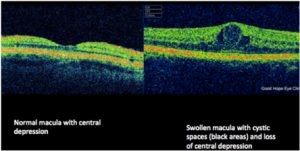

The fluid that leaks from the capillaries (small vessels in the retina) may lead to swelling of the central retina. This is known as “macular oedema”. It can be seen on instruments such as an OCT (optical coherence tomography). The image below shows a normal healthy macula and also a swollen macula (as seen on OCT).

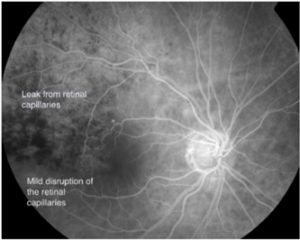

In some cases, the capillaries may become permanently damaged so that no blood flows through them, this is known as an ischaemic vein occlusion. If not, then it is known as non-ischaemic. The health of the capillaries has implications on treatment options and also the prognosis for vision.

This can be assessed by a test known as a fluorescein angiogram. This involves an injection of yellow dye into one of the veins in the arm or hand. By taking photographs of the eye after the dye has been injected, the retinal capillaries may be visualized.

Natural History and treatment options

On average, without treatment, 1/3 of patients may recover some vision (although this may take several months). A further 1/3 will remain relatively stable and the final 1/3 will deteriorate. The best judge of the potential for visual recovery, is the degree of vision loss at onset of the blockage. Usually patients with better vision, tend to have better vision at final follow up.

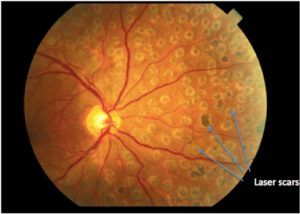

Laser treatment to the areas of capillary leak may increase the chances of vision recovery. On average, eyes treated with laser have a 2/3 chance of vision improvement (compared to 1/3, without treatment). This recovery may be protracted however and the laser may need to be repeated.

A further option involves injections of drugs (anti-VEGF) into the eye. These drugs are identical to those used in ‘wet macular degeneration’.

These agents work in around 2/3 of patients and the recovery of vision is rapid (around 1-2 weeks). In order to maintain vision however, these drugs may need to be injected periodically. The injections work by inhibiting fluid leakage from the retinal capillaries. As a result, the swelling in the retina is reduced, allowing the central retina to recover its normal anatomy. Unfortunately, when the drugs wear off, the swelling may recur, leading to recurrent visual blurring. In the event that this happens, further injections may be needed

OCT scanning may help to determine the need for further injections before vision loss occurs.

Central retinal vein occlusion

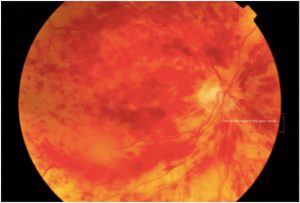

In CRVO the site of blockage cannot be seen, as it does not occur in the retina, but within the optic nerve. Bleeding and leakage of retinal capillaries is similar to that in BRVO but involves the whole retina, causing the whole field of vision to be affected.

CRVOs can also be non-ischaemic, but it is ischaemic CRVOs that are a potentially serious threat to the eye and its vision.

Ischaemic CRVOs are usually associated with very poor vision at onset. In this scenario, the chance of vision recovery is minimal, but regular review is required since, without treatment, 1/3 of ischaemic CRVOs may develop raised pressure in the eye and subsequent pain.

In this case, laser treatment may be considered to reduce the risk of pain in the eye, although this treatment does not improve the vision.

Sometimes anti-VEGF injections may be required.

Natural History and Treatment options

Similar to branch retinal vein occlusions, without treatment, roughly 1/3 of patients may recover some vision (although this may take several months). A further 1/3 will remain relatively stable and the final 1/3 will deteriorate. The reason for vision loss relates to swelling in the retina as well as reduced blood flow in the eye. Similar to BRVOs, injections in the eye may (anti-VEGF/ steroid) be helpful in reducing the swelling and consequently improving vision.

These agents work in around 1/2 of patients and the recovery of vision is rapid (around 1-2 weeks). In order to maintain vision however, these drugs may need to be injected periodically. The injections work by inhibiting fluid leakage from the retinal capillaries. As a result, the swelling in the retina is reduced, allowing the central retina to recover its normal anatomy. Unfortunately, these drugs do not unblock the retinal vein and as such, when the drugs wear off, the swelling may recur, leading to recurrent visual blurring. In the event that this happens, further injections may be needed

OCT scanning may help to determine the need for further injections before vision loss occurs.